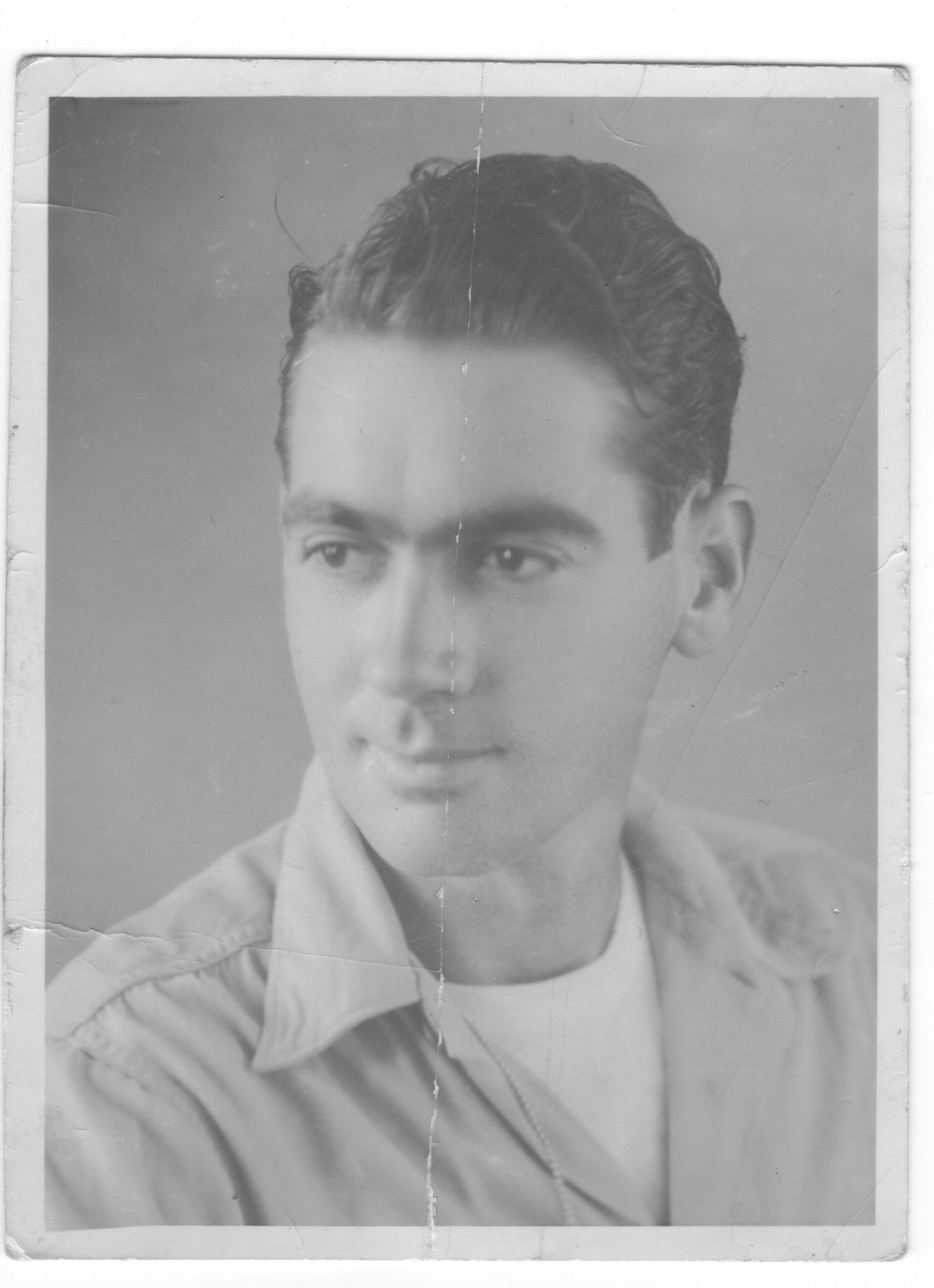

Leon Vincent Liedle

Leon Vincent Liedle

Lost at Sea; Body never recovered

19 August 1949

Leon Vincent Liedle

Grass Patch Football Club 1948

Leon Vincent Liedle was born to parents Bertram Aloysius Liedle and Ellen Mary Barnett on the 16 March 1921 in Nurse Loveland’s Place, Cottesloe. His Father was an Agricultural Bank Inspector (R&I) and they later moved to Salmon Gums, a small town 106 kilometres north of Esperance. He was an only child and attended school at the Christian Brothers’ College in Kalgoorlie. He enrolled as a Cadet Journalist with the “Kalgoorlie Miner” and completed his trade prior to the onset of the second world war. He was also a member of the “Grass Patch” Football Club.

Just prior to the outbreak of the second war, he joined a Greek ship as a cabin boy and learnt the basics of seamanship. He gravitated to other vessels over time and entered the Merchant Navy. In England he obtained three months’ leave of absence and during this time was engaged by the Minister for Information (M.O.I) to give a series of lectures to British workers on “Some Aspects of Australian Life”, and the work of the Merchant Navy under war conditions. He also broadcast a talk for the B.B.C. At the time. It was part of a broader campaign by the M.O.I to quash any propaganda efforts by the NAZI’s that Australia should break ties with Britain.

In October 1942 he was torpedoed in the South Atlantic when onboard the Liner Oronsay. He travelled 1080 miles in a lifeboat and was taken to Dakar in French West Africa where he was held in an allied detention camp on the Niger River, near Timbuktu. He was placed under the armed guard of the Vichy French. At the time, Goebbels was flooding French West Africa with lying propaganda designed to breed in the minds and hearts of the French suspicion and distrust of the Allies. Eventually, the radios in Dakar stopped tuning into German held Paris, and started tuning into the B.B.C, coinciding with Liedle’s release.

Later in the war he joined up with the small ships section of the U.S. Navy and as gunner in the bow of a small feeding tanker at the Leyte landing brought down a Japanese suicide plane which was heading for his vessel.

In total Liedle spent 8 years in the Merchant Navy in all types of craft.

In 1946 he was working in China with the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), an extensive social-welfare program that assisted nations ravaged by the war. The following year he returned to Australia to establish a new business venture. He purchased the Rangi, a 33-foot Bermuda auxiliary cutter built in Singapore which had made its way to Sydney under its own sail. Liedle’s intention was to refit the Rangi for use as a tourist cruiser for miners on holiday from the Kalgoorlie goldfields in the summer, and use it for commercial fishing in the winter months. Together with two other Merchant Navy men, Jack Taylor and Denis Raft, they set about the 5000 mile voyage from Sydney to Esperance Bay. In June 1947 they departed and charted a course via Cape York and Darwin, avoiding the Australian Bight due to the severe westerlies. The Rangi possessed a 24 horse power engine and 100 gallons of petrol, but these were only used when absolutely necessary.

Raft disembarked in Darwin and Liedle and Taylor continued on the journey which had been uneventful. By September they had reached Beagle Bay, 86 miles north of Broome where they anchored 2.5 miles from the coast. On the night of 15 September an explosion caused by petrol set fire to the vessel. The two men abandoned the vessel and rowed ashore in the ship’s dinghy, making for lights which they took to be Beagle Bay Catholic Mission. When they arrived exhausted and suffering shock they were cared for by a local Aboriginal camp who took them to the Beagle Bay Mission. The vessel was insured.

On the 19 August 1949, Liedle and his companion Hubert Richard (Dick) Cantwell (44) sailed their launch with a dinghy in tow from Esperance Bay to Point Rossiter (Wylie Bay), six and a half miles from the town. They anchored their launch about 200 yards off shore, on the north-east side of the headland and used their dinghy for reef fishing. The weather was rather rough, with a stiff south-easterly breeze blowing. At about 4:30pm a big sea swamped the dinghy, throwing both men into the water.

Cantwell was a strong swimmer, and told Liedle to cling to the upturned dinghy while he tried to reach the shore. Treacherous undertows kept him battling in the surf. After swimming for about 45 minutes he saw Liedle struggling behind him on the crest of a wave. Cantwell was almost unconscious when he was washed on to the rocks just 200 yards away from the capsized dinghy. When he recovered he walked six miles to the Goldfields Fresh Air League Hostel where the officer in charge of the home, Mr. Philippson immediately telephoned the Police. Cantwell was admitted to hospital at 8:15pm suffering from severe shock and exposure.

A search party headed by Constable William Dickinson scoured the beach. Oars and floor boards of the dinghy were found on the beach but there was no sign of Liedle. Don McKenzie assisted the search in his big launch. From Wylie Headland the dinghy was sighted, still anchored and floating where it was swamped. Liedle was just 28 years of age when he disappeared.

Rev. Father O’Leary travelled from Norseman and together with friends and family boarded the launch provided by Don McKenzie for a special posthumous service at the very spot where Liedle was last seen alive. As the Norseman-Esperance News wrote, “Seldom, if ever, into the history of Esperance has so many beautifully made wreaths ever graced the heart-shaped Bay of Esperance. They were cast on the calm waters in the vicinity of the recent tragedy in the form of a cross, after a most inspiring service by the officiating Priest.”

On 22 April 1956, Cantwell was Captain of the Railways Cricket team playing against the Incogniti team. He was making a fighting stand and had scored 26 when he collapsed at the wicket in the final of the Esperance Cricket Association. He died within minutes. He had played one first-class match for Western Australia in the 1924/25 season and was regarded as the “Father” of cricket in Esperance, where he had lived for 14 years.