Cervantes

Vessel Name: Cervantes

? (name unknown)

Loss of one crew member from hunger and exhaustion; 30 miles North of Moore River

29 June 1844

The Cervantes or similar Barque depicted in Colour Drawing

Depiction of the Cervantes Rigged as a Brig

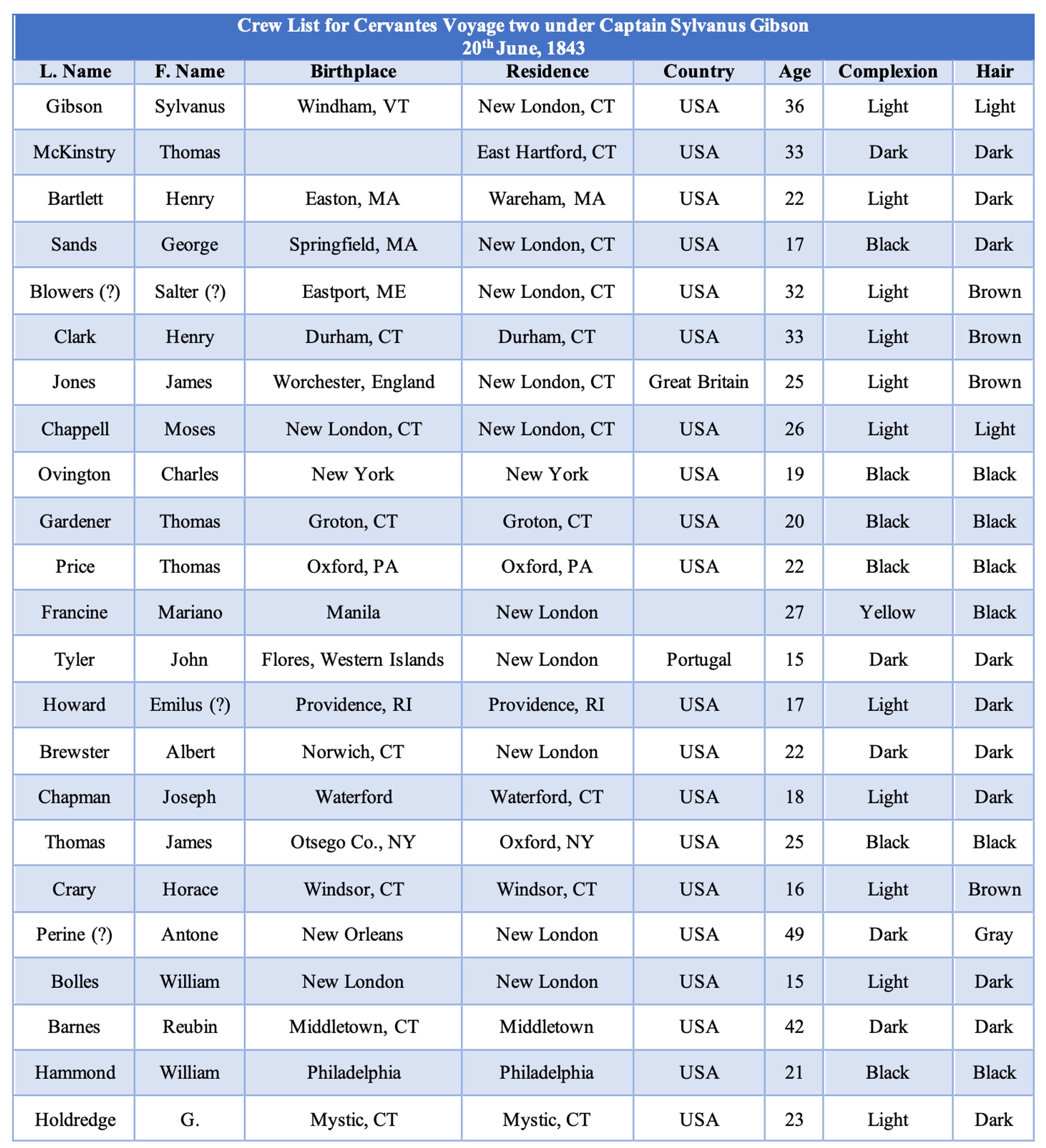

Cervantes Crew List 1843

Whaling was a global industry in the 19th century, fuelled by a seemingly insatiable demand for whale oil and bone. Wherever whales were to be found, there were whalers. The industry was dominated by Americans, operating out of the many ports strung along the New England coast - places like New Bedford, New London, Nantucket, Cape Cod, Provincetown, Westport and Boston. By 1846 there were 735 American whaling vessels, comprising 80 percent of the world's total whaling fleet. The whaling captains built themselves lavish homes, many with so-called widow's walks on their rooftops, from which wives watched and waited for their husbands to return from sea - and sometimes they'd be gone as long as three years. Many American whalers followed migrating whales into the southern oceans, with Western Australia's waters providing a bountiful harvest. In 1837 alone, they yielded over 30,000 pounds worth of oil and bone - and that was a lot of money in those days. The Cervantes was one such American whaler to visit “New Holland”.

The Cervantes was originally built as a whaling brig with one deck, square stern and a billet head. It was copper fastened and had a coppered bottom. It was built in Bath, Maine, and registered in that port on 4 October 1836. Dimensions listed on official records indicate that the Cervantes was 91 feet (ft) 9inches (28 metres (m)) long, 24 ft 5.5 inches (7.5 m) breadth, 11 ft 8 inches (3.5) depth and 231 tons.

The vessel’s owners were Richard McManus of Brunswick and Frederic G. Thurston of New York. The vessel was subsequently owned by a consortium consisting of Benjamin F. Brown, Jonathon Coit, Amos Willets, Samuel Willets, Nathan Belden and Sylvanus H. Gibson. They had it converted from a brig (2 masts) to a barque (3 masts) in June 1841, and the registration was changed from Bath to New London. The extra mast enabled smaller sails to be used without compromising the overall area of canvas available, allowing the ship to be manoeuvred by the few crewmen who remained on board while most of the others were out hunting whales in the whaleboats.

The first whaling voyage to Western Australia was in late 1841 under the command of Benjamin F. Brown. While in Albany re-supplying, three crew, Joseph Clark, John Morrison and James Wolley, deserted. After being captured and gaoled they escaped and hid, giving themselves up to the authorities after Cervantes had left port. They were each fined 10 shillings, in default of 10 days hard labour.

Cervantes returned home in May 1943 with 300 casks of sperm oil, 700 casks of whale oil and 5000 pounds of whale bone – a moderately successful trip for the time. Within a month, she was re-fitted and departed New London on 23 June 1843 with Sylvanus Gibson as her Master.

The Cervantes arrived off the coast of “New Holland” (Western Australia) in 1844. It was decided they would stay close to the coast for the winter and conduct bay whaling. The barque must have spent some time on the Western Australian coast, as it was in the Geographe Bay area during January and February of 1844. Despite this she had stowed only ten barrels of oil at the time she was wrecked.

On the 28 of June 1844, Cervantes was working about 16 miles off the coast of Western Australia near Jurien Bay, when the weather turned. Gibson directed the vessel into the shelter of a few small islands. The next morning the weather had cleared up and Cervantes began to move on as the wind picked up once more. Before the crew could take precautionary measures, the ship was struck against rocks and ran aground on a shallow sand bar located between the northern of two main islands on the inside of a reef, now called Thirsty Point.

The following morning, all crew members were able to leave the ship and make it to shore. As the location was remote, it was decided the crew would make their way to Fremantle, about 100 miles south. The Cervantes community talk about the crew taking a cask of rum with them. The first night of their walk the crew realized they would not be able to carry the rum with them without considerable struggle and so decided to finish off the cask that night.

The next morning the group woke with hangovers, and the bay was called Hangover Bay. Six of the 23 men decided they would have an easier time reaching Fremantle by boat and turned back to the ship to retrieve one of the whaleboats.

On the 6 July three men reached Fremantle, exhausted, and gave word of the ship's wrecking. Three days later Gibson arrived with the rest of the crew, save the six who thought to try their luck in boats and one who could not continue any further due to hunger and exhaustion, and was left about 30 miles north of the Moore River (about a third of the way through the entire trip).

Gibson asked the government for assistance by sending a boat, Champion, back to the wreck to gather up the captain and crews’ belongings and search for the missing crew members. The crew members in Fremantle were taken care of by the Resident Magistrate, Richard McBride Brown Esq. Brown was understood to be the Consul for the American Government and the brother of the Colonial Secretary. He would later become the Treasurer for the Fremantle Whaling Company in 1850 and arranged its sale.

When the man who was left north of the Moore River was found he was already dead and "eaten by wild dogs". This man was the only casualty associated with the disaster.

As the location of the ship was remote and far from Fremantle, the only place where repairs could be done, Gibson decided to put the wreck up for auction. At the time of the wreck, the population of Perth was less than 5000 with limited skilled tradesmen available to travel the distance to make the required repairs. Gibson explained that the ship had merely ‘broken its back’ but would still be in good condition for a while. He also pointed out that the area in which the ship was wrecked was abundant with seals. Messrs L. and W. Sampson, who owned an auction house in Fremantle, would conduct the auction on the 16 of July 1844.

The event was advertised in several newspapers but was not expected to make much money. She was to be sold in two lots: the chronometer on its own and the ship with all contents besides the crews’ personal belongings. The fact that the whaling gear had been refitted before this journey and had not been used much was publicised as a way to bring in more interest. It was suggested that the ship and gear could be used to start up a whaling and sealing venture near where the wreck occurred.

Mr Wicksteed bought the hull and its contents for £155. It was speculated that Wicksteed was not the actual buyer after suspicions arose when he paid the down payment of 20 sovereigns, and the next day paid the rest with notes and sovereigns, unusual at the time. The chronometer was sold for £23, showing how valuable the piece of equipment was.

Shortly after Wicksteed bought the wreck, he sent a team to investigate and begin recovery. They found the wreck as described by the crew. Their return was reported in the Perth Gazette on the 10 of August 1844, explaining they had recovered cables, anchors, a boat and some provisions and by their description Mr Wicksteed stood to gain more than triple the amount he paid at the auction.

Unfortunately for Wicksteed, Cervantes had a broken keel and could not be refloated. Despite intentions of starting a whaling venture near the wreck site, no evidence of the equipment being used for such an undertaking has been found. The hull was stripped of anything worthwhile and left in the shallow water.

On the 22 of July Gibson put an advert in the Inquirer, a newspaper based in Perth, extending thanks from himself and his crew for the kindness shown to them by the government and various individuals after the ship had wrecked. The loss of the ship was published in several newspapers throughout Australia, often in conjunction with the ship Halcyon—another American whaler lost on the coast of Western Australia.

The shell of the Cervantes was discovered in 1969 by Laurie Walsh while he was out chasing a turtle. He alerted the WA Museum. During excavation work on the wreck of the Cervantes, a small quantity of Pinctada maxima pearl shell from the north-west of Western Australia was found. This indicates the vessel visited the coast of that area, or that trade was being carried out with Aborigines. Perhaps a pearling industry off WA commenced much earlier than history shows, led by American enterprise.

In 1962 when names were being proposed for the townsite, the State Archivist advised the Nomenclature Advisory Committee that Cervantes Island had been named during the Baudin Expedition to Australia in 1801-03 and was presumed to be named after the famous Spanish writer Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra. Further investigation however showed that Joshua William Gregory in fact named the island after the whaler Cervantes in 1847 when he surveyed that section of the coast in the schooner Thetis. The wreck lies in 2 to 3 metres of water about 0.5 nautical miles West South West of Thirsty Point.